Scenes from a Dry City

A film about Cape Town’s water crisis raises profound questions about the character and stability of South Africa’s post-apartheid trajectory.

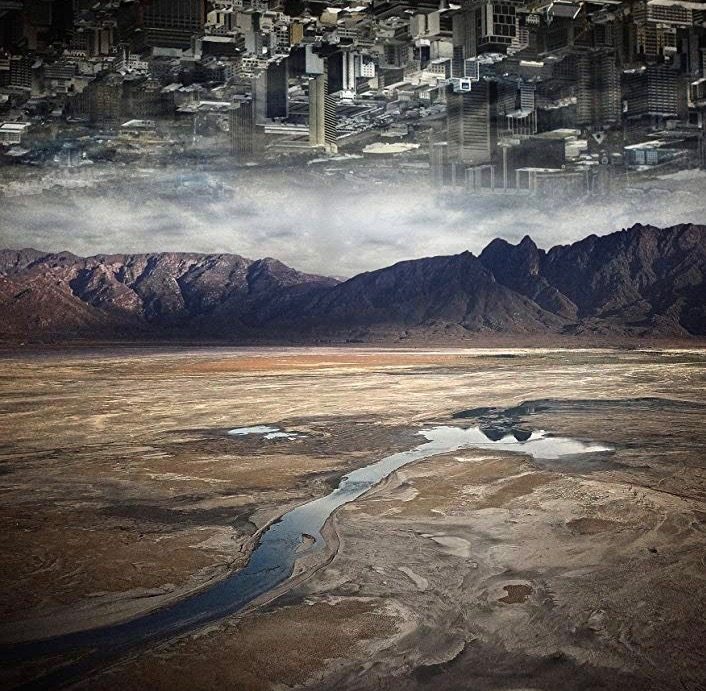

From the poster art for 'Scenes from a Dry City"

The documentary film, Scenes from a Dry City, can feel disorientating. It jolts viewers from shot to shot, often without clear explanation of the context. Those unfamiliar with Cape Town and its racialized political ecology might not be sure where to focus or how to interpret events. Disorientation, however, might be one of the François Venter and Simon Wood’s film’s strengths. It enables a porosity between past, present and futuristic dystopias that uses the relationships between water, the state and citizens to raise profound questions about the character and stability of South Africa’s post-apartheid trajectory.

The film’s focus is Cape Town’s water crisis. In 2018, the city made international headlines, as years of drought and possible mismanagement brought it dangerously close to being one of the first major cities internationally to “run out of water.” Despite almost reaching “Day Zero”, the moment when the taps would run dry, 2018’s heavy rains temporarily saved the city. While restrictions remain in place, the City of Cape Town has lowered them to Level 3, limiting consumption to 105 liters per person per day. This is more than double than just over a year ago, when the film was shot. At the time, with restrictions set at Level 6B, Capetonians were restricted to 50 liters.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the experience of the water crisis fragmented along the city’s racialized economic geographies. The film depicts these geographies in almost universally recognizable ways. Cutting between shots of outdoor toilets in township areas and images of wealthy suburbs, it illustrates how, even in moments of shortage, surplus appears to be available for the wealthy. More subtle, however, is how water usage and race shape relationships to the state. The film opens with an action sequence. The police are on the hunt for an “illegal” car washing business in one of Cape Town’s black township areas. Initially shot from the view of the police, viewers are brought into the narrative as if they are on a hunt. The targets are black men. As the police reveal their presence, the men flee. A few minutes later, we see police peering over the walls of working-class Coloured households to check for water infractions, entering properties to check their water usage.

The police’s interactions bring the past into the present. It is almost impossible for any South African above a certain age to see shots of police running after fleeing black men in townships to not have a deja vú moment of apartheid militarization of black residential areas. Similarly, the peeking over walls and entering home spaces echo urban legends of police peering through windows in attempts to catch couples breaking apartheid’s Immorality Act, which forbade sexual relations between people of different racial categorizations. What Scenes from a Dry City draws attention to then are the perpetuation not only of the racialization of resources that characterized apartheid, but the longevity of the securitization practices that accompanied this. In contrast to these securitized relationships, we introduced to a wealthy white suburban resident who is getting a borehole drilled so that she can preserve her garden. No police interrupt, even though, by January 2018, borehole usage was meant to be monitored. While frustrating and life changing for all Capetonians, restrictions only transformed into violence for some.

With these haunting images of race and class inequality marking the viewer’s experience, the film ends on a fundamentally ambivalent note. At certain moments, in others we are proffered possibilities of hope. A protest against the privatization of water suggests push back against the market logics that perpetuate historical inequality. Those familiar with post-apartheid South African politics will know that the struggle against the privatization of water and electricity has been one of the period’s most prominent areas of mobilization. However, the protest seems to go nowhere. We are rapidly taken back to someone driving a golf cart through lush green lawns. Despite mobilization, surplus remains in privatized, largely white, wealthy spaces. Inequality initially appears overcome in the idyllic scenes of cooperation shown at the Newlands Spring. This public water source, located in an elite Cape Town neighborhood, for years not open to everyone, appears to bring people together. People of different racial categorizations stand side-by-side to collect water. Gradually, however, the viewer realizes that some of the Black poor are collecting and transporting water for wealthier white residents. Equality turns out to be a myth, racialized labor relations persist.

As the film draws to a close we are presented with the only genuine but fleeting moment of community building – a mass prayer meeting. South Africans from a variety of backgrounds congregate against the pending apocalypse. As the rain suddenly returns and rescues Cape Town, the film suggests that only divine intervention might resolve the city’s, and, indeed, the country’s problems. Scenes from a Dry City, therefore sends a profoundly ambivalent message. That change is possible, but that the existing practices of politics however, will not be the ones to deliver it.