A particular kind of black man

The Nigerian-American writer, Tope Folarin, wrestles with blackness and black immigrant identity in his new novel.

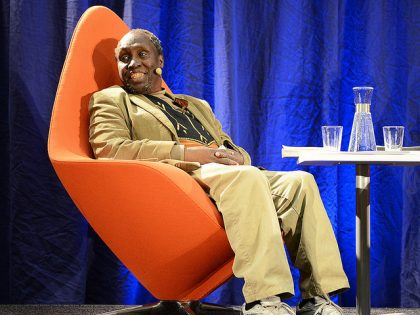

John. Image credit David Robert Bliwas via Flickr CC.

Tope Folarin became, for me, a literary voice to follow after I read his essay, “To Be Where We Are,” in the fall 2015 edition of Transition Magazine. Two years before, in 2013, Folarin won the Caine Prize for African Writing. But, his win was met with much debate, the thrust of which was: Could this man, who was born and raised in America, and has never set foot in Nigeria, claim a Nigerian identity and win a prestigious literary award in the name of said claim?

“To Be Where We Are” reads like a response to that debate. Folarin writes beautifully, that creation is working on itself in him. “What does it mean if I say to you that creation is working on itself inside me?” he continues:

Well, it means that I am made up of the stuff of the universe, like everyone else. Stardust and starlight and words and images and America and Nigeria and Africa and who knows what else. It also means that these familiar components have assumed new forms within me, that to spend some time with me is to glimpse possibilities that have yet to manifest themselves in our shared reality.

It’s a remarkable insight, one that I reach for in mild jest when I encounter Instagram skits of “African parents” that recall little of my childhood, and in desperation when I fear that my Nigerianness, already tenuous in some settings, has been irrevocably eroded by my years in a mostly white, liberal United States. “Preach, Brother Tope! Speak that truth!” my heart yells. This notion—that social categories are not fixed as traditional thinking suggests, but that each of us, in living, come to clarify and reveal the possibilities in them—how liberating!

How true.

In a sense Folarin’s debut novel, A Particular Kind of Black Man, is the story of a young man’s difficult journey to this insight. That boy, Tunde Akinola, is born black in the United States to parents who at the time of their arrival are so insufficiently attuned to American realities of race and difference that when they are deciding where to settle, they make the tragically human decision to premise desires for isolation over other considerations, e.g. “Are there other black people there?” or “Is this a sundown town??” They land in predominantly white, small-town Utah.

American race drama ensues. There is a racist neighbor, though her breed of racism is uniquely Mormon. Kids at school don’t understand why the brown won’t come off Tunde’s skin. Tunde himself starts to wonder about the brown won’t come off his skin and about his hair’s natural kinkiness. In the midst of this, mother becomes seriously ill with schizophrenia. Folarin does not explicitly identify the stress of migration and racism as a factor in the emergence of her illness, but one cannot help wondering. He does carefully lay out schizophrenia’s painful effects, the violence and upheaval it unleashes on the family.

Ultimately, Tunde’s mother returns to Nigeria. He is left with his father, a man working through his own relationship with America, as the primary source of love, identity, and a sense of home. (There is also, briefly, an unhappy stepmother, but Tunde never finds her love despite his best efforts). Mr. Akinola does point his son to “a particular kind of black man”—Sidney Poitier, Hakeem Olajuwon, Bryant Gumbel—as model for how to be. Yet, while he studies these men and makes himself in their image, Tunde knows that they “do not match what is on the inside.”

Outside Tunde’s home, the world is in as much disarray. There is no stable definition of black boy, or later, black man for him to inhabit. Depending on where he looks, to Fresh Prince, to his little brother, to his friend AJ, to other black kids in a new school, what it means to be black moves and slips. Tunde moves through these shifts with a longing that is moving to witness, and an unrelenting bewilderment that comes off naïve as he grows older.

By the time he is 18 and at Morehouse, the renowned HBCU, he makes a leap in insight and starts to intuit that he has been putting his energy in the wrong place all this time: “I decided that the problem was that I spent my entire life trying to fit in one box or another; I decided I needed some time to figure myself out.” Folarin’s wisdom about identity shines here, as he reminds us, through Tunde, that the more significant human task is to come to know oneself well, rather than rely on social categories alone for a sense of identity.

At the same time, Tunde has begun suffering from double memories and worries he may have inherited his mother’s schizophrenia. What follows is, for me, one of the most poignant passages in the book, for how it weaves the disorientation of double memories with the disorientation of modern identity tasks:

It’s hard to explain but I’ve always felt like I’m supposed to be somewhere else. I have no idea where that somewhere else is, or how I’d even get there, if it’s some other place or time, but I know it’s not here. I’ve never admitted these things to myself because I always hoped that I’d figure something out, because what’s the alternative? The alternative is the way I feel now: lost, bewildered, terrified.