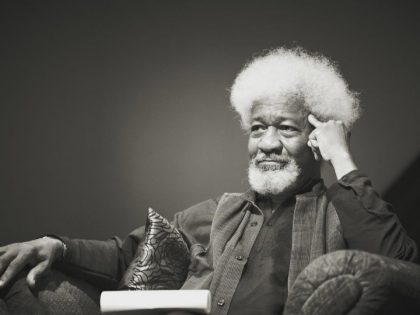

Wọle Ṣoyinka pulls Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, his third novel, out of a very deep well of passion, turbulent but empowering, for a writer pushing 90. It is a novel by turns angry, perplexed, and cynical, yet effusively solicitous of a principled outlook on life. The themes here resonate with those of the Nobel laureate’s dramas of moral decay (Madmen and Specialists, Opera Wonyosi, Requiem for a Futurologist). Stylistically, the novel is closer to his post-1998 prose works and the memoirs, especially Ibadan: The Penklemes Years and You Must Set Forth at Dawn. Years ago, Ṣoyinka told an interviewer, Jane Wilkinson, that “the novel for me is not a very congenial form…I don’t even like the novel [and]…the kind of fiction which I really enjoy is good science-fiction.”

Reading this unusual novel clarifies his reasons. His achievements here, it seems, are those of a writer unable to trust any other form to bear the weight of his desire in accounting for the state of things in his homeland. This is fictional Nigeria, assuming that isn’t a tired tautology, a story about everything that is happening in a country caught in the crosshairs of unimaginable events. Religious terrorism—alias Boko Haram—operates in lockstep with unhindered kidnapping, illegal gold mining fuels widespread insecurity even across the borders, and the predatory teeth of the powerful sharpen themselves on the entrails and other body parts of the powerful-to-be. Ṣoyinka simply sets it all down, even at the risk of doing violence to novelistic conventions best suited to his narrative.

A drama of colorful characters, from the religious charlatan Papa Davina (alias Teribogo, alias Gardener of Souls), supremo at Villa Potencia, to Sir Goddie Danfere, the Prime Minister not too overwhelmed by matters of state to ignore petty social intrigues, to Chief Modu Udensi Oromotaya (proprietor of the morbidly named National Inquest). There is the counter-force known as the Gong o’ Four—Badetona (The Scoffer), the surgeon Kighare Menka, Duyole Pitan-Payne and Farodion—the last of whom is missing in action since their parting in college, until a sleight-of-hand reference reveals his identity in the novel’s final pages. There is The Family, comprising the three siblings of Duyole, his first son, and the patriarch, Otunba Pitan-Payne, alias Pop of Ages, the collective antagonist in the thriller that takes up one-fifth of the novel. There are the women, too; each passionate and steadfast, none too misty-eyed to be sold a lie.

Duyole Pitan-Payne, “engineer and non-conformist man of business,” has a new position at the United Nations, and he visits the seat of government to meet Sir Goddie, ostensibly to be celebrated for the recognition. But a plot is afoot—one so thick and subterranean even this self-aware man of the world has no idea of its existence, let alone its dimension. Why does the shrewd Badetona take to his heels at the mere sight of the inner (or outer?) sanctums of Villa Potencia, only to lapse into eternal silence after a spell in detention? Is there more to the membership of a lodge shared by the prime minister, the Otunba, and Papa Davina? Why would the prime minister give a private audience to a foreigner engaged in illegal gold mining? What is the connection between the “business proposition” to Menka by three shadowy visitors and the fire that soon obliterates Hilltop Manor, his club-cum-residence? Everything is happening, but nothing is as it seems. Homeless overnight, Menka accepts his friend Duyole’s invitation to relocate to Lagos—to Badagry, in fact—and the two briefly renew their faith in the Gong and its lingo, which is “more reliable in gesture, tone and context than meaning specific.”

The reunion is an opportunity for Duyole to start tinkering with the Codex Seraphinianus, the secret code of the cartel behind the traffic in human body parts, whose emissaries recently accosted Menka with the business proposition. In his line of work as a surgeon, Menka has had to operate on the victims of Boko Haram bombings and Sharia scalpels. He has seen all the horror. Despite his and his friend’s jaded views of human life in Nigeria, however, they never imagine the level of degradation at which the cartel operates. Cracking the code becomes a matter of duty, if they must restore a semblance of life to the values that they have spent their long friendship cultivating. With Badetona silenced, and Farodion unaccountably missing, the two Gong members come to stand for the novel’s protagonist. A blast goes off in Duyole’s study moments before he breaks the code, as though his fingers are the ones on the fuse. The remaining two-fifths of the novel takes up the saga of seeking medical help for him abroad and, failing that, bringing the body home for a decent burial. All in the face of implacable opposition from his family.

The bombing is an insider job. The Family is in it up to its neck, although with the exception of Damien, Duyole’s son, we are not shown exactly how. It is enough that Otunba’s preferences cast a spell on everyone. In a move that readers familiar with the moral universe of Soyinka’s work will readily recognize, Menka takes up the challenge of saving his friend’s brittle life, going through a series of episodes like a sequence from a crime thriller. The friendship between him and Duyole will rank among the most exemplary in African literature. If literature is a reflection of the rhythms of linguistic life, “tight from heaven, like Duyole and Menka” ought to be an idiom about friendship. The surgeon’s lack of family (nuclear or extended) contrasts sharply with Duyole’s, although it becomes clear, as the drama of saving his life unfolds, that the latter’s natal community is resolved to undermine everything he stands for.

Slightly short of five hundred pages, Chronicles is a gushing narrative, perhaps overly so. There is not a single timorous moment. Every page of it crackles with the barely restrained rage of a writer at the end of his patience, but constrained to seek release in high humor, the kind he has spent an entire career perfecting. The range of celebratory Nigeriana is on view here, the world of multiplying acronyms inhabited by a people for whom, it seems, happiness is invented. The Festival of the People’s Choice. Brand of the Land. Yeoman of the Year. People’s Award for Common Touch.

The first section of the chapter titled “The Scoffer’s Progress,” seen from Badetona’s point of view, reveals a cynical but profound insight into the psychological aspects of Nigerian life. Papa Davina’s profile is something of a charlatan’s itinerary, and the reader comes away with the chastening knowledge that this morally vacuous person was once part of the Gong o’ Four.

In another moment, daily existence is no more than “…a cozy cohabitation between two religions which, a mere kilometer or two from that very spot [the presidential villa], held each other by the throat to be piously squeezed or slit at little or no provocation.” At yet another unnerving moment, a character observes: “We are ringed by new abominations every day, acts you never could have contemplated in your youth–all have become commonplace.” None of these denies Chronicles its fragrance. Moments of pleasant surprise appear, such as the affectionate detour on classical music, and a thumbnail focus on Austria. The long, somewhat Kafkaesque exchange between Menka and a man in the dark before Hilltop Manor burns down is reminiscent of the Indonesian shadow play. A brief but intense reflection on female grief shows the depths of empathy to which Ṣoyinka plumbs to ameliorate what may come across as an excessive focus on starring males.

Like Ṣoyinka’s two other novels, The Interpreters and Season of Anomy, this is written from an omniscient perspective. Unlike them, there is an undertone of sarcasm throughout, rising to an overtone of exasperated cynicism. In one sense, it is an indication that this is a work of satire, fitting for the company of the plays mentioned earlier. One could go so far as to claim that, other than Opera Wonyosi, The Beatification of Area Boy, and the volumes in the Interventions series, Chronicles is the next thing Ṣoyinka has written that is so totally invested in the political and moral puzzle that is Nigeria. It is, for that reason, deeply committed to a utopian vision, and there is nothing odd in seeing utopia in a satirical work, for the one is always secretly active in the sphere of influence of the other.

In another sense, the style is better suited to a narrative in the first-person perspective. That perspective would be Menka’s, the closest person to Duyole (who, in a way, looks like a revised version of Ṣekoni, the visionary engineer in The Interpreters). In fact, it is conceivable to think of Menka as the novel’s central character, the one endowed with the greatest narrative authority. A native of Gumchi, a fictional town in Plateau State, Menka is also about the closest Ṣoyinka has moved to creating a non-Yoruba protagonist, far from the singular avatar based on Ogun, the Yoruba deity that serves as the metaphor for his creative idealism.

Perhaps this was the point of that literary conceit all along: to fashion a creature of sensibilities from a given culture and set if free of the original mooring because hallowed be all earth, including rocky, backwater Gumchi. Urban Jos, one of Nigeria’s most cosmopolitan cities, is Menka’s professional home, but it has also become a site of heedless ethnic and religious violence over the past decade. His reflections are everywhere touching and heartfelt, and the arresting description of the fire at the Hilltop Manor goes on for over two pages of closely observed detail, entirely from his point of view. The sections of the novel that put the thoughts and desires of these friends at the center are always the most compelling and emotionally rewarding. Menka may turn out to be the writer’s best-realized character, irrespective of genre.

A drawback of the style is that, except in a few minor cases, all the characters are wily, cynically knowing or opaque, and only intentions separate compassionate characters such as Menka from venal ones like Papa Davina and Sir Goddie. There are consequential differences between the Nigerian and US editions of the novel, but still, the sprawling storytelling could have used more control and proportion, skills that the author typically commands. In an ethical gesture to one of his abiding critiques, Ṣoyinka chooses to place the Pitan-Payne family home in Badagry, the better to focus on the legacies of Atlantic slave trade. It is odd, though, to contemplate the notion of any African family deriving its fortunes from the slave trade. Status maybe; African receipts in the trade were mostly on the order of an impossible exchange.

Ṣoyinka has written and published continuously for over 60 years, and he has everything to show for it. A novel of this kind, in scope and depth, at this stage of his career is a surpassing achievement. Even if Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth were the only thing that he ever wrote about Nigeria, it would be sufficient.