Not so quiet resilience

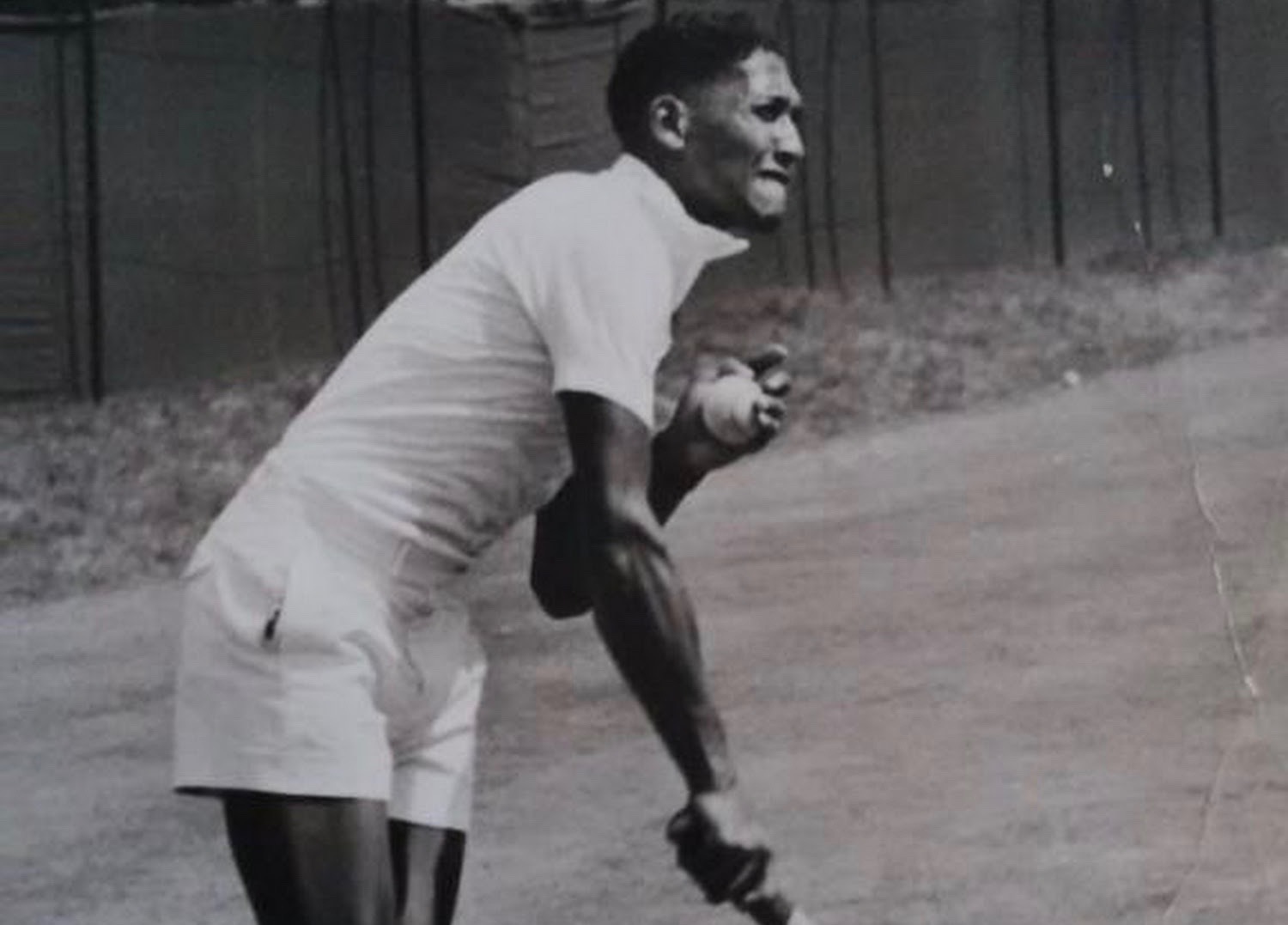

David Samaai was the first black (and coloured) South African to play at Wimbledon in 1949. He was 21 years old. He did so before the Americans, Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe.

Image via Herri Foundation Courtesy of the Samaai family ©.

The governing body of world tennis is the International Tennis Federation. It organizes games between professional players, ranks them, and sanctions tournaments. This includes junior players. Every year the top juniors compete in a series of graded tournaments around the world. The first tier is known as the junior “Grand Slams.” Like with the senior circuit, this refers to the four traditional open tournaments played at Wimbledon, in France, the US, and Australia. Below these four are a group of six “Grade A” tournaments. One of these Grade A tournaments is played every October in Cape Town, South Africa. In 2019, that tournament was renamed the David Samaai Junior Open.

David (Davey) Samaai was the first black (and or coloured) South African to play at Wimbledon in 1949. He was 21 years old. He may well be the first black or African tennis player from anywhere in the world to qualify for Wimbledon too. He qualified again in 1951, 1954, and 1960. His best performance was reaching the third round in 1954. In addition, he also played in the French, German and Swiss Opens. While overseas, he also won several smaller tournaments (mainly in Britain), and played against several of his white countrymen who he wasn’t allowed to play at home and beating some of them convincingly, including the captain of South Africa’s all-white Davis Cup (national) team, Gordon Forbes. As Samaai would later describe his game against Forbes; it was “a match which could never have materialized at home.”

In June 2019, a few months before the announcement of the David Samaai Junior Open, Samaai died at his home in Paarl in the Western Cape Province. He was 91 years old. At the time, Gavin Crookes, then-CEO of Tennis South Africa (the body that runs organized tennis in South Africa), said this about the renaming the Grade A tournament in Cape Town after Samaai: “Whilst this tribute will never adequately recognize the challenges he had to overcome as a black South African, playing in an era that was strictly amateur, as well as the achievements he attained as a top player in the world of tennis, I have little doubt the fact that these trophies will be presented to two of the top juniors in world tennis will go some way to making him proud – in his quiet and modest way.”

Crookes’ praise aside, it was his reference to Samaai’s “quiet and modest way,” that is telling.

Despite Samaai’s singular achievement – at a time when South Africa’s whites-only regime intensified its oppression of the majority black population – he is hardly mentioned in popular discourses about sports, especially in local and international media, and the legacies of racism in South African sport and society. And his achievements are not well known outside tennis. When Samaai is celebrated, there is, like with Crookes, a lot of talk about his quiet resilience.

The silence in popular media and culture, especially the country’s legacy white sports media, around Samaai’s incredible achievements is even more depressing given that he played at a time when black tennis players hardly featured internationally.

If you google “who was the first black (or African) player to compete at Wimbledon,” references to Althea Gibson first come up. Gibson, a black American tennis player who was born in the same year as Samaai, 1927, first qualified for Wimbledon in 1951 when she was 23 years old, two years after Samaai had already played at Wimbledon. She went on to an illustrious career, winning the Wimbledon women’s doubles championship in 1956 (with an Australian partner) and then won the women’s singles title in 1957, becoming the first black or African person to win a Wimbledon or any Grand Slam title.

When it comes to men’s tennis, in most tales of tennis history, Arthur Ashe, another American tennis player, is credited as the first black male player to compete at Wimbledon. Ashe first played at Wimbledon in 1963, fourteen years after Samaai, and would go on to win the Wimbledon men’s singles title in 1975, making him world number one that year. Ashe started competing as a professional in the late 1950s and would become the first global black male tennis star. He is still the only black or African male tennis player to have won at Wimbledon, the US Open (1968) or the Australian Open (1970). The only other black male player to win a Grand Slam singles title is Yannick Noah in 1983. Noah struggled at Wimbledon though; his best showing was in the third round. (Incidentally, Noah’s father, Zacharieh, was a professional football player from Cameroon whose team won the Coupe de France in 1961. After Zacharieh’s retirement, Yannick Noah partly grew up in Cameroon where he started playing tennis.)

Of the leading male players still active, the best performance of Gael Monfils of France (his father is from Guadeloupe and his mother from Martinique, immigrants from France’s “departements” in the Caribbean) was a fourth round showing at Wimbledon in 2018. Jo Wilfried Tsongo, also French (his father is from Congo-Brazzaville), has been to the semifinals (2011 and 2012) and quarterfinals (2010 and 2016) of men’s singles at Wimbledon.

None of these players come close to the achievements of Serena Williams, who has won 23 Grand Slams, the most by any player in the Open era, including seven women’s singles titles. Williams is arguably the greatest tennis player of all time, male or female.

One reason for omitting Samaai’s achievement as the first black African player at Wimbledon, may be that American narratives about everything – including designating who was “the first” at anything – dominate in the black world. Another may be that Samaai downplayed his achievement. Samaai’s biographer Michael Le Cordeur writes that Samaai detested being referred to as a “coloured tennis player.” It may also have something to do with how coloured people are viewed in South Africa; in some accounts they are not counted or don’t count themselves as black. However, there is no evidence that Samaai had anti-black politics. In fact, after he retired from tennis, he played a leading role in school sport organized by SACOS, known for its boycot stance vis-a-vis apartheid segregated sports and for forging a political consciousness among black (this included coloured and Indian) sports people at grassroots level.

A much more plausible reason may be that tennis is hardly considered a mass sport – whether in South Africa or elsewhere. However, Samaai’s own involvement in tennis as a player and administrator and the deep well of organized tennis culture in coloured, Indian and African townships under apartheid, undermines that popular perception. Samaai’s father, for example, played tennis in the 1930s, belonged to a club in Paarl and later built a tennis court for his sons in their backyard. Samaai himself met his wife on the court and they played mixed doubles together in amateur tournaments organized by a well-coordinated national coloured tennis association around the province and the country. Nevertheless, to this day, most South Africans experience tennis as a TV sport happening somewhere in Europe or North America, living vicariously through Venus and Serena Williams or Roger Federer (whose mother is a white South African; Federer, incidentally, was also Samaai’s favorite player).

Tennis, like other modern sporting codes, came to South Africa with colonialism. Unlike those others, tennis as a game became more associated with white elites and with money. The cost of playing (finding a court, court fees, equipment, the right attire) was prohibitive. As a result, tennis never developed the political or social connotations of sports like cricket (with English South Africans and false notions of equality), rugby (Afrikaner nationalism and white resilience and triumph in the face of international criticism of Apartheid) or soccer and boxing (with black mass participation, fame and some class mobility) under Apartheid. It is worth mentioning that sports like rugby and cricket have deep histories among the black population that parallel or even predate that of whites, but that the idea that black people came to them late, persists.

As for professional tennis in and from South Africa – both under apartheid and now – it is mostly white players who represent the country overseas. Even when South Africa was the subject of sports sanctions, white players still played overseas. The ITF ostensibly banned South Africa from international tennis, but the country still fielded all white Davis Cup teams into the late 1970s after the ITF let South Africa qualify via the Latin American region. (In one case, in 1978, when the sports boycott movement against Apartheid nearly derailed a Davis Cup tie between South Africa and the USA in Nashville, Tennessee, the white South African Tennis Union recruited a 18 year-old coloured tennis player, Peter Lamb, then on a college scholarship in the United States to the team to deflect criticism of its racist policies. It was all a publicity stunt to deflect. They had no intention to play Lamb.) On top of it, white South Africans weren’t banned from competing as individuals internationally. As a result, players like Forbes, Cliff Drysdale, Ray Moore, and later Johan Kriek and Kevin Curran, still played world tennis on the ITF circuit throughout and right till the end of Apartheid.

South African tennis thus took on a very white and very exclusive image, which it still does to a large extent even after Apartheid. The combined effect of these media constructions and how the game was organized was to obscure tennis’ appeal among the black population and their role in its development as a sport. Samaai’s story is wound up with the independent tradition of black tennis and is a corrective to these misconceptions.

Samaai was born in 1927 in Paarl, a medium-sized town in wine country about an hour’s drive to the northeast of central Cape Town. Paarl is the largest town in the Cape Winelands, an area which foundation is built on slavery at the Dutch Cape Colony. It was also where Afrikaner nationalists plotted to rewrite the history of the Afrikaans language as white instead of a vibrant creole. Davey was the oldest of seven sons. The late 1920s was not a good time to be born black in South Africa, less so to imagine a career as a black tennis player. While Apartheid would only be formally introduced after 1948, the Union of South Africa – the white-run state – was already implementing a slew of new discriminatory laws limiting black advancement.

Samaai’s parents, John and Sophia, were of modest income, but owned a house at 19 Du Toit Street in Paarl’s downtown. In 1950 that section of town would be declared a whites-only “group area.” The Samaais held on for another nearly two decades, before they became the last family in the area to be forcibly removed to a nearby coloured township.

John Samaai, according to Le Cordeur, was “a competent social player.” By the 1950s, there were five tennis clubs in Paarl with mostly coloured members, and John was a member of the Ivy Lawn Tennis Club. John naturally introduced his eldest son to the game, andt it helped that the family lived next to a tennis court. Davey started hitting the ball with his dad at the club from around 5 years old. It soon became clear that he had a feel for the game. Davey complimented his father’s training with street tennis played with wooden bats. At some point, John Samaai built the family their own tennis court in their backyard and Davey practiced there with one of his brothers, Frankie.

Not long after, Davey began to compete at club level, playing with a borrowed racquet. (He only got his own racquet when he went to play overseas.) When Davey was 18, he was already national champion (the South African Coloured Tennis Championship) of the South African Tennis Board, which organized the game amongst coloureds. He would retain that title for the next 21 years. (A sidenote: Samaai was a talented sportsman; he also got provincial colors in rugby.)

As he couldn’t try himself against the best local white tennis players who enjoyed better facilities and training, he decided he would try his luck overseas. According to Le Cordeur, Davey’s form should have made him an automatic choice for the 1949 Davis Cup team, but apartheid denied him this honor. “For the first time, Davey felt that apartheid was standing in his way to greater success” and that it was time to try his luck overseas. (Later in the UK, he beat South African Davis Cup players like Abe Segal, Gordon Forbes and Cliff Drysdale in practice.)

Samaai would talk about the level of competition among his cohort of coloured players: “I have no doubt in my mind that we would have beaten any other white club in South Africa had we had the chance to show of our skills.”

Davey’s trip to Europe was fundraised from the local coloured community. When he arrived in the UK, he received an invite to visit the Dunlop offices in London, where he was given six tennis racquets as a sponsorship. At first he struggled on the English grass courts, but soon settled in, becoming known for “his big forehand, scorching backhand, fearsome serve, balance, anticipation, impeccable net play, speed around the court and stamina.” One of his first victories, along with his English doubles partner, Colin Hannan, was a victory over a white South African duo, N. Cockburn and S. Levy. A number of other victories over white South African players, who he was prohibited from competing against back home, followed. Davey’s supporters in the coloured community followed his progress closely via the local press and when he played Forbes in 1954, “were buying newspapers everyday to monitor his progress.”

To get into Wimbledon, you had to be nominated by your country association. Davey could expect no help from the white tennis establishment at home to make this happen. He had to earn the right by playing in a series of smaller qualifying tournaments in the UK, which he did. In his first try at Wimbledon in 1949 he was beaten by an Australian, Jack Harper, 6-1, 6-4 and 6-3 in the first round.

He would qualify again in 1951. During the same year, he made it to the second round of the French Open. (It is unclear if, apart from being the first black South African to play in the French Open, he was also the first black player from the African continent to do so.) In 1954, which witnessed his best performance at Wimbledon, he ended up playing his third round match on center court, where he lost to Australian Ken McGregor. This match was his “career highlight” and obviously served to showcase black tennis from South Africa on a global scale.

In 1960, at 32 years old, Samaai qualified for Wimbledon for the last time. But by then, his priorities had changed. He had married Winnie, his longtime girlfriend and mixed doubles partner and started a family. Although Samaai would make a few more trips to Europe to play in club tournaments and back in Paarl played in competitive tournaments well into old age and after Apartheid ended, he switched his priorities to teaching for which he had qualified before he left for Europe the first time. He threw himself into the teaching profession with the same dedication he showed to tennis.

Michael le Cordeur’s book Davy Samaai The People’s Champion despite its title and cover image (Samaai hitting a backhand at Wimbledon), spends as much time detailing Samaai’s long career as a tennis player, but equally as a teacher, choir director and his being instrumental “in broadening access to higher education for the rural Afrikaans speaking community.” Le Cordeur, a professor of education, ascribes Samaai’s success to his family dynamic (two other brothers, Ronnie and Gerald, had fame as performers and artists), to his local community, and “because he led by example.”

Le Cordeur’s book is not the usual sports biography. Text is interspersed with photographs (giving a scrapbook effect), verbatim testimonies by friends and relatives (his children, grandchildren) and clippings from old newspapers. The result is a celebration of Samaai’s life. (Even Samaai’s funeral is extensively covered.) Le Cordeur writes in the introduction that the current generation don’t know who Samaai was “because our history has been deleted from the mainstream media in South Africa, which refused to acknowledge what Davey and people like him did to liberate South Africa.”

Le Cordeur wants to “take ownership of our sport and education, and to take back our space.” I suspect what he is referring to, but he doesn’t elaborate, so we don’t know exactly what Le Cordeur planned to do. At some level, however, Le Cordeur’s call to take ownership, gels with the call to decolonize knowledge, which by itself is a worthwhile undertaking and which has gained impetus in South African history writing and in popular discourses about South Africa’s past.

As a player, Samaai wasn’t viewed as particularly politically radical. He felt his tennis should speak for him. Nevertheless, Le Cordeur describes him as a “loyal member” of the South African Council on Sport or SACOS “in their fight against discrimination and apartheid.” (SACOS was founded in the early 1970s to coordinate anti-apartheid sports among black sports bodies explicitly opposed to Apartheid, many dating their origins back to the 1880s. SACOS’ leadership was close to the sports boycott movement in exile and locally to black consciousness, Trotskyist tendencies and the Pan-Africanist Congress and later some elements in the United Democratic Front. SACOS advocated for “no normal sports in an abnormal society” and rejected any sponsorships or state support that implied segregation. It was prominent until the end of the 1980s when it was overtaken by the National Sports Congress, a new sports coordinating body which was effectively the sporting arm of the ANC. A proper history of SACOS still needs to be written.)

A British journalist who interviewed Samaai for a short profile in 1961, described his relations with the white South African tennis contingent as “cordial.” When pressed, Davey said: “I hope they are not embarrassed by having me here. I don’t think they are, do you? We seem to get on very well together. When I arrive, everyone wants to know, ‘How did you get on with the South African players.’ My answer will always be ‘we are very good friends’.” In his last match in the UK in 1961 (a tournament in Birmingham), Samaai and his doubles partner, John McDonald from New Zealand, played against the white South Africans Ian Vermaak and Berti Gaertner in the final. The matchup was significant, as it was “the first time a non-white South African had ever played against white South Africans in a tennis final.” For context: back home the white South African government of Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd had decided to leave the Commonwealth over a demand that it end Apartheid and instead declared a whites-only republic. It had also begun to imprison and banish to exile its main political opposition in the ANC, Communist Party and the Pan-Africanist Congress.

Samaai and McDonald won the game and afterwards the two white South Africans, according to Le Cordeur, “seemed completely at ease with this quiet, dignified man.” Le Cordeur quotes Samaai (it is unclear when) saying that after the match the three players discussed politics and the white South Africans wanted to know “both sides of the story.”

Today people would call that false equivalence.

Samaai then told his white countrymen “my personal opinion of things,” that “I would not come here and criticize our government’s policies. It wouldn’t be the right thing to do. After all, I am South African.”

It may be that he was either apolitical and didn’t have a framework to understand what was going on in South Africa or he did, and was too scared to take the political risk. Le Cordeur’s decision to project this as a beacon of forgiveness on the part of Samaai and Vermaak and Gaettner is a stretch (“these tennis players had reached reconciliation 34 years ahead of what was called the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1995”).

Which brings me back to those characterizations of Samaai as “quiet and modest” and a “quiet, dignified man.” At some level it feeds a notion of coloured political (and sports) actors as nobly long-suffering and meek, and ultimately apolitical, as opposed to rowdy and troublesome blacks. The problem is Samaai’s actual life doesn’t gel with that. Later in Davy Samaai The People’s Champion” in a short chapter, Le Cordeur documents some of Samaai’s life as a sports administrator and simultaneously activist against Apartheid sport and building alternative sports structures. It is also where we get a semblance of Samaai’s sports politics which was far from quiet or dignified. Samaai played a key role in the formation of the Tennis Association of South Africa (TASA), who played under the SACOS banner, helping to grow tennis in mostly coloured townships. Also, Samaai was associated with figures like Frank van der Horst, Hassan Howa and Eddie Fortuin, all SACOS leaders and associated with a strident anti-apartheid politics.

Samaai and other TASA leaders and coaches rejected attempts at bribing them, refusing to be forced into doing “what was against their principles.” Following unification between white and black tennis in 1999 to form the TSA, as a sign of how imperfect the process was (to a large extent it kept old class and racial inequalities intact in the sport), Samaai became vice president and Crookes president. That same year, President Thabo Mbeki awarded David Samaai the Presidential Sports Award for Lifetime Achievement.