Coming to voice in Cuba

Thanks in part to the internet, Black women in Cuba are now able to forge space and create visibility for themselves.

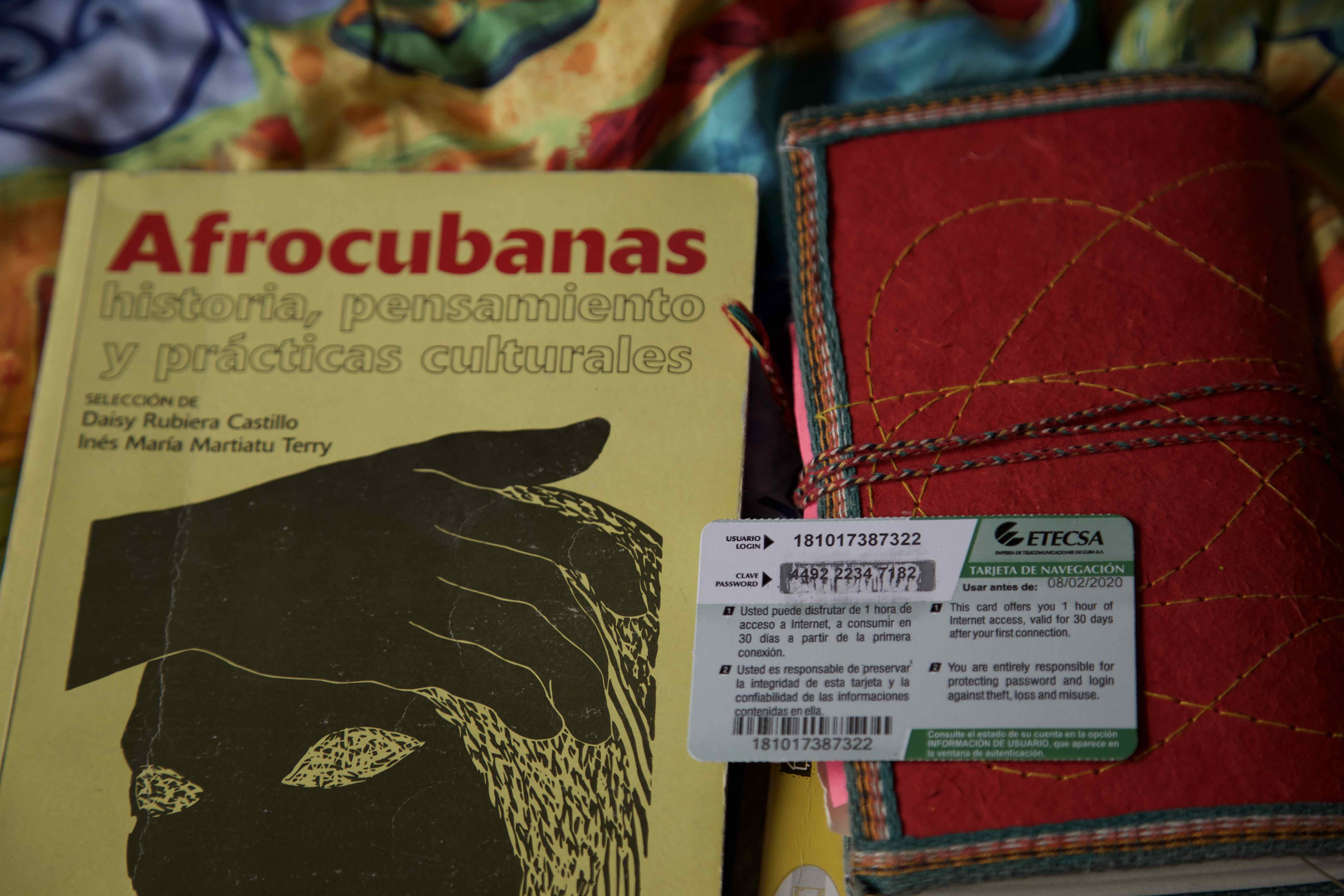

Image: Aliyah Blackmore.

The history of black bodies in Cuba is deeply interconnected with slavery, exploitation, systems of oppression, and the arguable emancipation of these oppressions through the 1959 Revolutionary process. University of Havana economics professor, Esteban Morales Domínguez, writes that the relics of slavery and colonialism – which encompassed “prejudice, negative stereotyping, and discrimination” against black people or non-white Cubans – moved from the colony to the Republic and while the Revolution attempted to undo this history, racism was only suppressed and silenced, rearing it’s head with the onset, post-Cold War, of the Special Period in the 1990s.

I spent two months in Cuba last summer. One afternoon as I walked along the Malecón, Havana’s famed seawall, I started talking to a local, Ronald. To my surprise, our conversation about race was extremely direct. As I talked about my own experiences with race and racism in the US, he blurted out that “it is hard for us here.” He pointed to his skin and then to me and said, “…and even harder for [people like you].” He meant for black women.

I was navigating my own racial and gendered identity – as an Afro-Caribbean womxn born in the United States – in Cuba, a country where anti-black racism was often not acknowledged or widely discussed. In addition, historically, in Cuba, there has been little room for the voice and identity of Black Cuban women.

In varied social interactions, I witnessed how welcoming and approachable Cubans were toward white or non-black people, but showed some resistance to my presence or that of other black women. Before traveling to Cuba, I had spent much time with the words of poet, Georgina Herrera, among other writers, and the visuals of filmmakers Sara Goméz and Gloria Rolando, deepening my own understandings of Black Cuban identities and seeing the ways in which black women in Cuba were asserting their voices by and for themselves.

With the Cuban Revolution (1959) came the Federación de Mujeres Cubanas (the Federation of Cuban Women), to reassess and redefine the role of women in society, as well as in land redistribution, and literacy campaigns in efforts to reorder the nation and give voice to those communities and identities, which had been historically oppressed.

Notably, Che Guevara’s 1965 letter, “Socialism and Man in Cuba” puts into motion a shaping of Cuban identity that exists monolithically and in surrender to the state. What became central to building a socialist discourse and new man/woman in Cuba was the moral and spiritual commitment to the nation. But do the relics of slavery, oppression and inequality, particularly for Black Cubans, and Black Cuban women, disappear that easily? In a conversation one afternoon towards the last weeks of my time there, a Black Cuban woman said to me: “…Remember, Cuba was one of the last nations in the Caribbean to abolish slavery [in 1886].”

Social structures upheld by the euphoria of the 1959 Revolutionary process began to fall apart—inequalities silenced and buried beneath revolutionary discourse and rhetoric re-emerged as the economy collapsed. As Roberto Zurbano, a Black Cuban writer and activist, argues, the dual currency (one pegged to the US Dollar) has only proliferated social inequalities, such as racism and discrimination.

The racial situation in Cuba has affected black women in a particular way, as they have suffered exponentially because of gender, extreme poverty, and race: a “triple discrimination.”

Black consciousness movements of Latin America and the Caribbean Diaspora (i.e. Garveyism, negrismos, and negritude movements), created and in some ways renewed an interest in black identity, histories, culture and voices, previously excluded, however most understandings of the black woman “focused on her beauty and her external physical features,” according to Gabriel Abudu, a professor of French at York University in the US, who studies Cuba. The recovering of, or “rehabilitation” of, the black female identity always “manifested itself” in illuminating her sensuality and capacity of “sensual love”—the female solely perceived as another element in a “[exotic] tropical environment” and disregarded any thought beyond her skin color. This can be seen in newspaper ads which “praised” the strength and infinite abundance of the black woman during slavery, like in volumes/issues of Carteles magazine of the 1950s, or in the writing of poet Nicolas Guillén, himself of mixed descent and a prominent figure in the Cuban state after the Revolution. The speaking of and for the black woman created a “voicelessness” rooted in the history of representations in which she was the object. Writers such as Excilia Saldaña, Georgina Herrera, and Nancy Morejón, for example, during and following the Revolution, asserted their identities as Cuban, black, and woman—all three simultaneously.

As the editors of the 2011 edited volume, Afrocubanas: historia, pensamiento y prácticas culturales, wondered: “[d]ónde queda la realidad historico-social de la mujer de color/negra [where does the historical and social reality of the women of color/black woman exist?]

Through the internet Black Cuban women are creating and accessing a wider network of imagining identities that intersect with and challenge the layered political and social grammars of the Revolution in the present.

Journalist Sara Más suggests that while the black female in Cuban society remains the least visible, this voicelessness has been subverted by the emergence of informal internet spaces that make visible the stories and experiences of Black Cuban women in the diaspora. Whether through blogs or Twitter, black female journalist, artists, essayists, rappers, and poets have begun to make visible their experiences, making way for possibilities of engaging with the nation from black or afro-feminist perspectives, exploring Cuban identity through the intersections of race and gender. Blogs, such as Directorio de AfroCubanas, TUTUTUTU-Un boletín para la mujer lesbiana afrocubana, or Negra Cubana Tenía Que Ser, have allowed for the negation of the stereotypes that have historically been associated with black women and are initiating a “coming to voice” of these identities through the digital sphere.